7 Utah County Ghost Towns and the Fascinating Stories Behind Them

Utah County is brimming with fascinating history, abandoned ventures, and little-explored corners. Among the overlooked curiosities in Utah County are its many ghost towns. Here are the fascinating stories behind seven of these Utah County ghost towns.

Colton

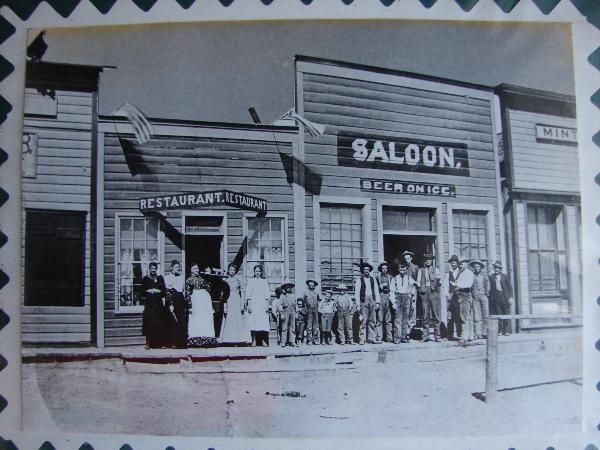

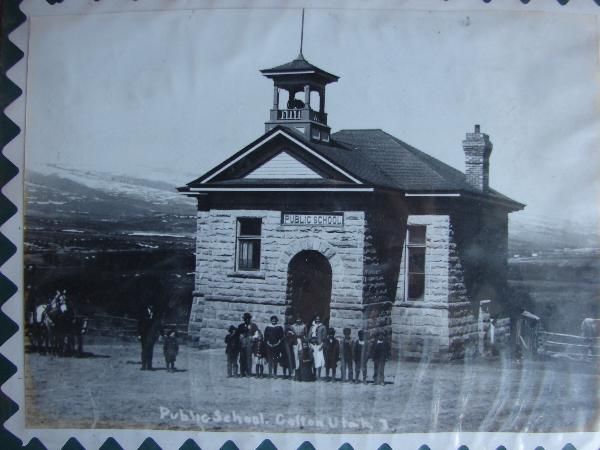

Six miles south of Soldier Summit you can find foundations and remains of a ghost town that lived and died with the railroad. In fact, the town was given its name, Colton, in honor of railroad official William F. Colton. Though also a mining town, Colton’s real lifeline was the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad.

Settled in 1883 under the name Pleasant Valley Junction, Colton eventually grew to become a thriving town with a hotel and five saloons. On May 1, 1900, the town was shaken, but not shattered, by the Scofield mining disaster in the town of Winter Quarters just 20 miles away. The disaster killed more than 200 men, leaving behind 107 widows and 268 fatherless children, making it the deadliest mining accident in American history up to that point.

In ensuing decades, Colton experienced its own misfortunes as it was burned and rebuilt three times. In 1904 new life was injected into the town when notorious robber and gunfighter Clarence L. “Gunplay” Maxwell discovered ozokerite near the town and started what would become the largest known ozokerite mine in the world. But Maxwell soon moved on from Colton, eventually becoming embroiled in several robberies throughout the West.

With the spread of diesel locomotives, Colton gradually declined until all that remained was the Hilltop Country Store, which was relocated to UT Highway 6, and a few ruined buildings to attest to its history.

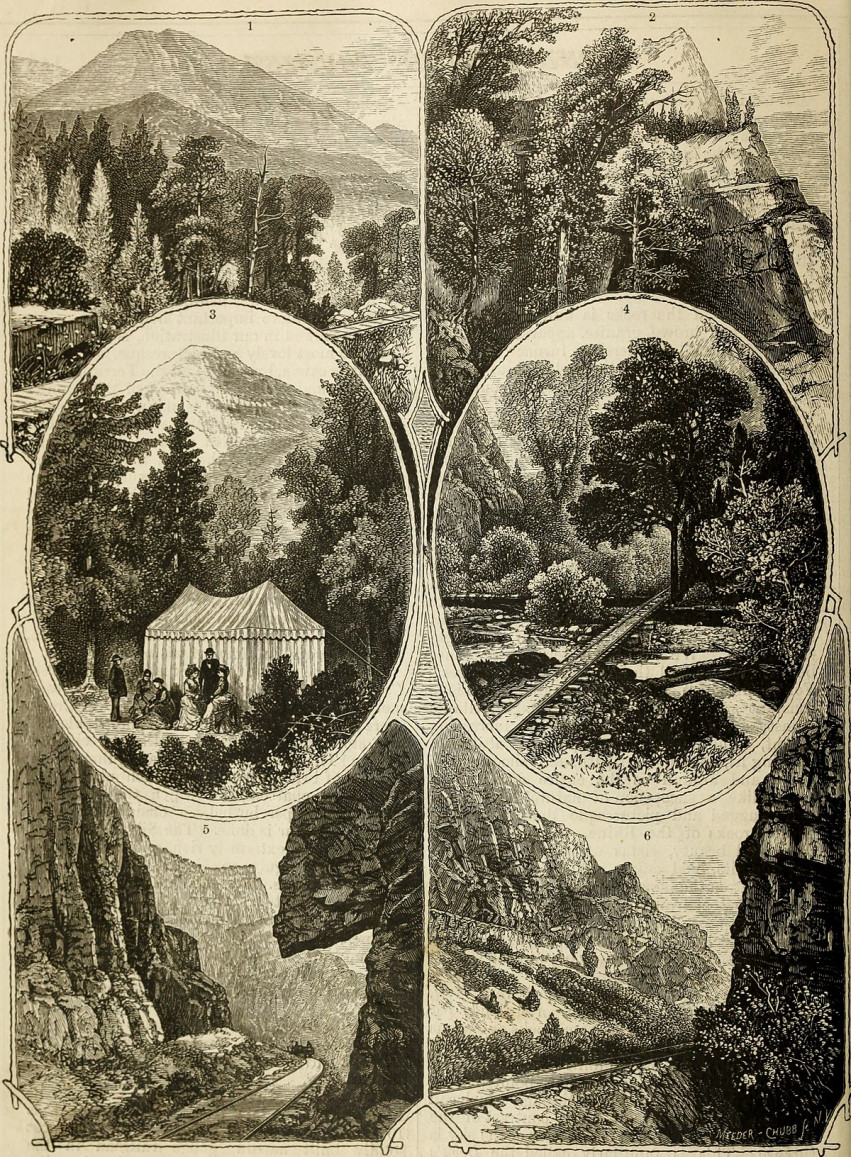

Forest City and Deer Creek

High up American Fork Canyon rests two ghost towns, Forest City, built in a valley called Dutchman Flat, and Deer Creek, which used to sit where Tibble Fork is today. Once a silver mining town, Forest City hosted a sawmill, two general stores, hotels, and a saloon, but the town lasted less than a decade.

In 1872, a diphtheria epidemic spread through the town after severe weather set in, and the dead were buried in a small cemetery known as Graveyard Flat. Later, the American Fork Railroad, which was supposed to provide transportation to and from the mine, was stopped short of the town due to engineering difficulties.

Transportation costs for the mine rose too high to make operations profitable, and the town soon died off with the mine. Deer Creek sprung up around the upper railroad terminal in American Fork Canyon but lasted less than a decade, similarly dying off with the mine that supported Forest City.

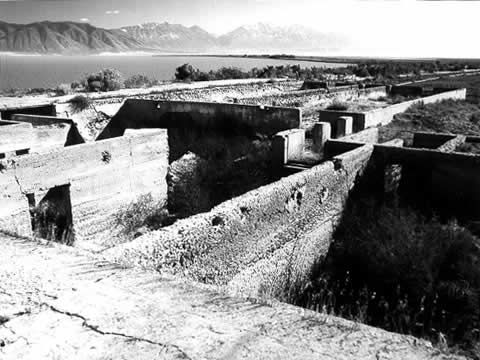

Mosida

On the southwestern side of Utah Lake sits a ghost town that was once touted as a quaint oasis of peach orchards. Mosida’s unique name is an amalgamation of the last names of the men who originally purchased and began developing the land in 1909 (R. E. Morrison, Joseph Simpson, and J. E. Davis). A company later bought the land and built a pump house and series of irrigation ditches to make the orchards fruitful. After building a luxury hotel and planting 50,000 trees, the company ferried possible investors across the lake in a fine passenger boat.

The extravagance and promise of Mosida brought 400 people to the community, but disaster soon struck. The fluctuation of the lake levels made the pumphouse and irrigation ditches too expensive or ineffective, the soil proved too mineral rich for orchards while grasshoppers wreaked havoc on other crops, and the Mosida transportation boat was destroyed by fire in April 1913, isolating the town even further. By 1917, less than a decade after its inception, Mosida had few residents left. By 1924, Mosida was completely abandoned. Today, ruins are all that’s left of Mosida, including the foundations of the hotel and schoolhouse and the concrete pumphouse walls.

Pelican Point

The cape-like Pelican Point is a feature many who live on the west side of Utah Lake recognize, but what you may not know is that this geologic feature was once a mining and fishing town as well as the location of “one of the most nefarious and publicized murders in Utah history,” according to the Daily Herald.

Headlines across Utah decried “The Deed of a Monster” and “A Ghastly Find” when three corpses washed up on the thawing shores of Utah Lake within one week of each other in April 1885. The victims were cousins Albert Enstrom, Alfred Nelson, and Andrew Johnson, all shot in the head with a .38-caliber pistol. The three had been missing since February 17. It was later discovered the three young men had been killed while tending livestock at a cabin near Pelican Point and their bodies dumped in Utah Lake through a hole in the ice. A wagon, horses, and goods had been stolen from the cabin.

Harry Hayes, Albert Enstrom’s stepfather, was eventually convicted for the murder and sentenced to be hanged June 16, 1896. The night before Hayes was to be hanged, the new Provo sheriff, George Storrs, interrogated Hayes all night and became convinced Hayes was innocent. Storrs persuaded Governor Heber Wells to commute Hayes’s sentence to life imprisonment while he continued to investigate the murder. After tracking down the stolen goods from the cabin, Storrs unwound a series of crimes and murders that all linked back to a man named George H. Wright, who went under various aliases in states across the West and Midwest. Wright, who then went by the name James Weeks, was linked to this and other murders, but he continued to evade custody and eventually disappeared. Hayes was absolved and released after serving four years in prison.

Though always a small town, Pelican Point eventually shrunk and then died, along with the rumors about the three murders.

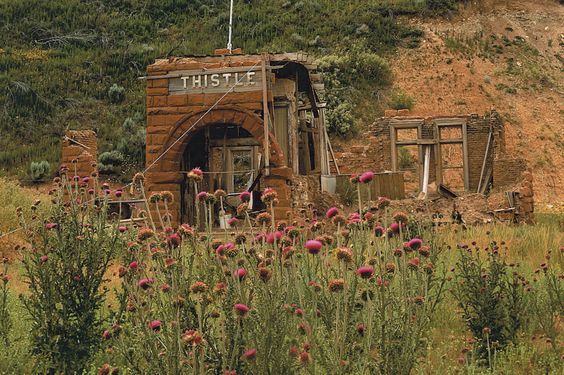

Thistle and Mill Fork

The towns of Mill Fork and Thistle up Spanish Fork Canyon both sprang up in the later 1800s around the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad. Both towns’ economies were closely linked to the railroad, and when diesel engines changed railroad stops, routes, and needs, Mill Fork became extinct while Thistle began to dwindle.

All that is currently left of Mill Fork is a cemetery near UT Highway 6 that holds the remains of children who contracted Scarlet Fever at the mining camp of City Creek, those who died violently in railroad accidents, and even the victim of a murder/suicide, according to the Daily Herald.

The town of Thistle ended abruptly in 1983 when the entire town was evacuated and eventually destroyed after heavy rains and fast-melting spring snow turned the hills above the town into a mass of moving mud.

The mud plugged the narrow canyon floor, creating a 220-foot-high wall and a lake that drowned the town. The landslide became one of the costliest landslides in United States history. Though the water eventually drained and the state built a dam upstream of the town, Thistle has remained abandoned ever since. Now all that remains are a few ruins and water-logged homes.